My wife and I did some amazing things over the summer. We spent a lovely few days at the Greenbrier resort in West Virginia, we enjoyed an amazing weekend at the Wilds, a nature preserve owned by the Columbus Zoo, and we traveled to Louisville and toured several bourbon distilleries. Bourbon has been my spirit of choice for some time, and I have always been amazed by the variety of product, but had never really studied the process. This weekend proved very enlightening and revealed some striking similarities to the art I practice.

To be a bourbon, the product must be made in the United States, contain at least 51% corn, age in white oak, charred barrels and be distilled to a certain proof. The magic occurs in the remaining 49% of ingredients (which can be barley, wheat, etc.), the degree of charring in the barrel (ranging within 5 levels from a light toasting to something that resembled fish scaling), and the time spent in the rickhouse (where the barrels are aged in a non-regulated environment for up to 7 years). One of the reasons that 95% or the world’s bourbons come from Kentucky is the natural high-quality water supply (occurring over a natural limestone shelf), and the climate that offers extremes (especially in summer) in temperature. This environment-aging is what gives the bourbon it’s color and flavor. A series of mild summers might give the whiskey a more mellow taste, extreme summers might provide more vitality, as the spirit is drawn in and out of the charred wood in the barrel. Another intriguing part of the process is the life of the barrels. After the bourbon is removed for bottling, the barrels go to a distillery in Scotland to age scotch whisky. After that process, they may be used for wine, and from the winery, they go to the Caribbean to age rum, then to Mexico to live out their usefulness aging tequila. Reincarnation as an oak barrel might not be a bad existence!

We started our tour at Stitzel Weller, one of the oldest distilleries in Kentucky, having the license number of 16 (they are now in the 20,000 range). Pappy van Winkle, a venerable name in bourbon distilling, was the Master Distiller here for many years. Stitzel-Weller defined the craft, endured prohibition (distilling whisky for medicinal purposes) , survived the downturn in bourbon consumption during the 60’s when everyone was drinking martinis, and now create a blend that contains a small portion of Pappy’s old recipe. One of the most impressive aspects of this property is the research and development lab, where the process is continually refined.

From Stitzel Weller, we went to the Kentucky Artisans Distillery, which was the reason for our trip. I had recently sampled Jefferson’s Ocean for the first time at the Greenbrier and wanted to learn more. The bourbon is crafted in a relatively small operation that boasts 2000 barrels a year (Makers Mark does more than that in a day). Once it has aged for a while, it is then put on a research ship and continues to age at sea for 6 months. The salt air and the movement of the ocean create a unique aging process that turns the spirit into a very intriguing bourbon. Each batch, however, is different as one voyage may be calm while another may encounter rough seas. The consumer can visit the website and read the ship’s log to see what the conditions were like during the bourbon’s voyage.

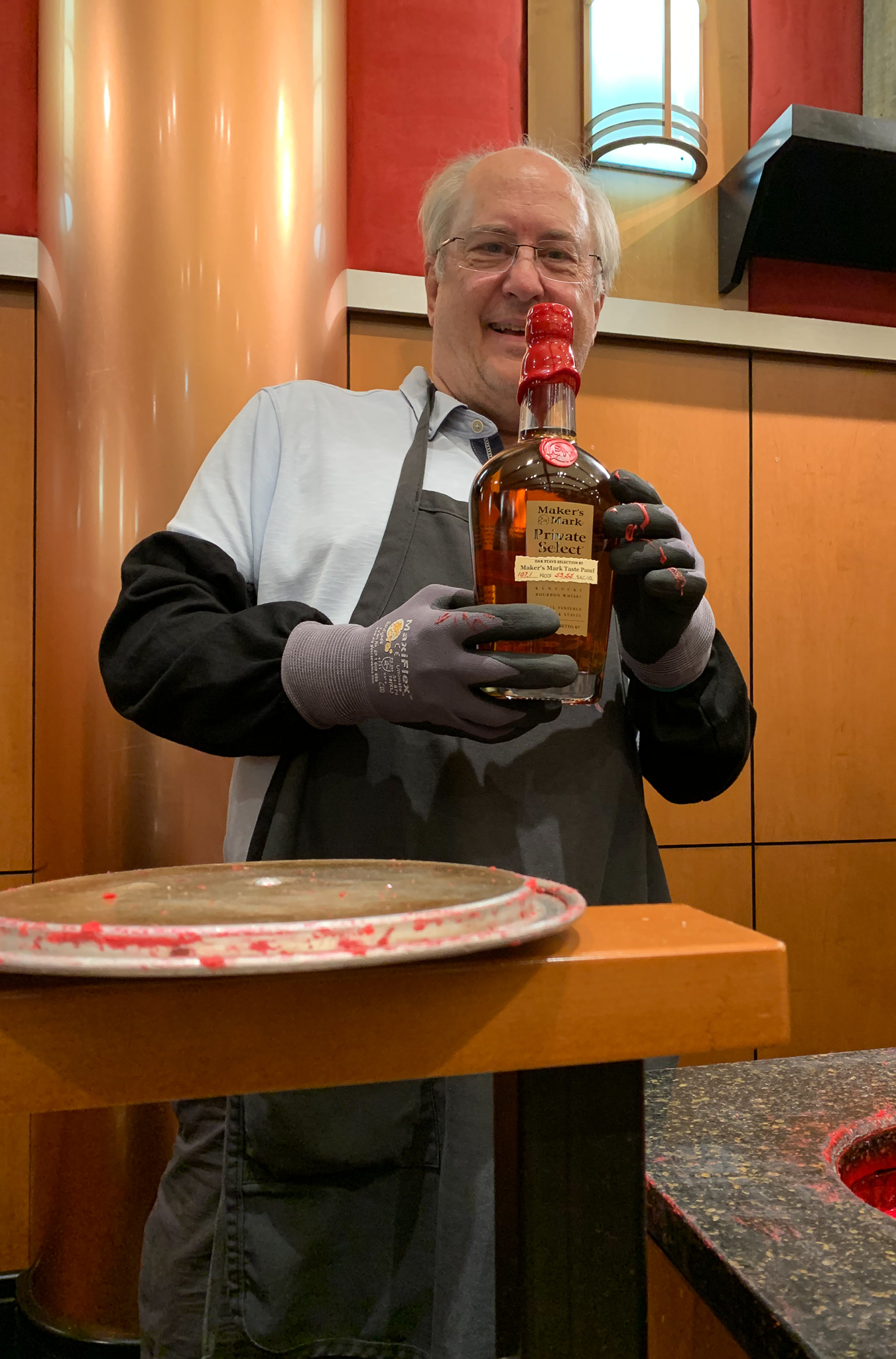

Finally we visited Makers Mark, one of the larges purveyors of bourbon on the planet. Their vast campus in the town of Loretto is immaculate, and they periodically offer exhibitions by regional artists in addition to their resident works by Dale Chihuly and other prominent artists. As luck would have it, our visit coincided with an exhibit by Stephen Rolfe Powell, a glass artist from Danville Kentucky. Upon arrival we were met by Whisky Jean, Makers Mark resident mouser. We then enjoyed a tour of the facility that concentrated on the art as well as the production process. I had heard that this was the best tour on the Bourbon Trail, and we certainly agreed. While the production is massive, the place has a very homey feel, and its commitment to art.

n 2014, Makers, along with Jim Beam and Knob Creek were acquired by the Suntory Corporation in Japan. I have heard grumblings from arts organizations that the new owners do not share the commitment to philanthropy that their predecessor company, the Beam Corporation held. Time will tell, I suppose, but the facility’s commitment to visual art is impressive.

Making fine bourbon is certainly an art. One refines and perfects a craft and then waits for the muse to descend to inspire the final work. There is a lot of perseverance involved, a lot of monitoring and refining. Like the evolution of a conductor, the process is long and arduous, patience is necessary, but the final product is worth the effort.